The following was previously published in the 2019, Issue-2, of the Retiree Guardian. It is published here with the permission of the author, Don Warsavage.

Don Warsavage’s ‘Person-to-Person’

Telephone People

We were a culture.

Through the years of developing and maintaining the Bell System, our dedication to service defined us.

We were called “Ma Bell.”

Perhaps that quality started with our founder. After growing up in Scotland with a mom who was nearly deaf, he became a teacher of people with hearing impairments. He taught in three schools for the deaf in Massachusetts and Connecticut.

As a scientist he pursued the unique theory that the words from our mouths might be carried to the ears of distant listeners by the phenomenon known as electricity. Of course we all know it was Alexander Graham Bell.

Throughout our history, millions of us were employed by the 22 operating companies, Western Electric, and Bell Labs under the umbrella of AT&T.

The hard wires that connected the whole country together; the central offices and the machines inside; and the very telephones that sat in our homes were all owned by “Ma Bell.”

Our achievements were significant. Astronomers can see the shape of asteroids. They know the precise orbit of the planet Mercury around the sun. They learned many secrets about our universe that could not be revealed by traditional telescopes. It is because of the work of Karl Jansky of Bell Laboratories. In the 1920s he was researching why static interference was obstructing telephone transmission. He discovered the field of Radio Astronomy.

In New York City, on April 7, 1927, Walter Gifford, President of AT&T, squinted into a tiny screen less than three inches square. He was watching the black and white image of the Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover. Hoover was speaking from Washington, D.C. Gifford watched and listened as Hoover said, “Today we have, in a sense, the transmission of sight for the first time in the world’s history.”

It was called, “radio vision,” developed by Bell Laboratories.

In 1948, William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain of Bell Laboratories were awarded the Nobel Prize for the development of the transistor that launched the age of solid state electronics.

Many telephone technicians were granted deferments from the draft in World War II because they were regarded as essential to maintain our telephone network for national security.

In the Cold War, telephone people by the hundreds were used, working with the U.S. Air Force to build over fifty radar stations, all north of the Arctic Circle. It was the famous D.E.W. line (Distant Early Warning System.)

In addition to being our own culture, we were also a monopoly.

Keenly aware of that fact were all the front line workers: the service reps, the telephone operators, the linemen, installers, cable splicers, combination men and repairmen and their bosses. When service was interrupted customers had no other place to go.

Attempts were made to help with customers who had difficulty paying their telephone bill so they could avoid being disconnected for nonpayment.

One telephone exchange manager in a small town stood in a muddy beet field, talking to a local migrant farmer. The farmer’s ordinary nominal monthly bill for a single phone on a four party line had ballooned to over three hundred dollars with excessive long distance charges.

The farmer spoke very broken English. The man-ager had only a limited knowledge of Spanish. They worked hard at trying to understand each other.

After many hand gestures and repeated phrases with different words, the manager learned what had happened. The farmer’s troubled teenage daughter had run away to Mexico. Homesick and afraid, she called her frantic parents back home many times. As it turns out, neither the farmer nor his wife understood what the operator meant by the word, “collect.”

A deal was worked out. The farmer kept his service with the agreement he would pay five dollars per month extra until the charges could be paid off.

Another exchange manager developed a unique collection strategy. On Friday evenings he stuffed his pockets with unpaid bills and his “paid” stamp and headed out to the town’s most popular bar. There he would collect cash from some of the locals as they shared a few beers. He was very popular and had success in clearing up balances.

The following tale exists in rumor only. It has not been verified.

The exchange manager in a small New Mexico town had constant difficulty with a wealthy resident who always resisted paying his bill. He had shut off his service several times always resulting in an angry row.

When the bill was several months late again the manger had reached his limit. He drove out to the man’s house. He loaded the man’s brand new motorcycle onto his pickup and hauled it back to the telephone office. He contacted the recalcitrant customer and told him if he wanted his motorcycle, come down to the office and pay his bill.

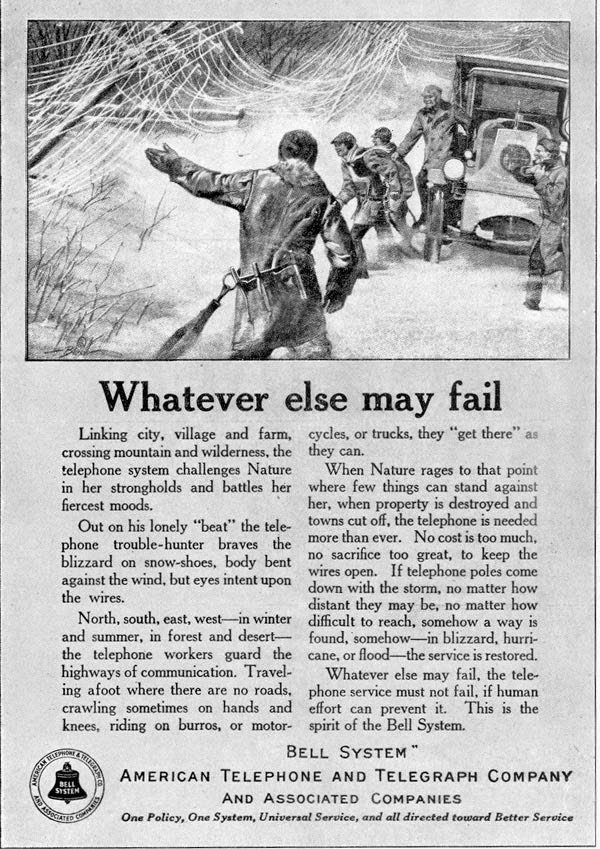

Over the years poles fell and wires were broken and tangled by floods, storms and other disasters. Thousands of heroic efforts have been recorded of telephone people in their attempts to restore service.

In June of 1940, the residents of Winnebago Nebraska were awakened during the night by the howl of the town’s warning siren. One by one each of their phones began to ring. It was Nellie Lazure, the all night operator telling them in a hurried voice, “Leave your home! A flood is coming at us down Omaha Creek!”

Nellie was calling from her switchboard. It was in a one story house in the lower part of town. Some residents called Nellie back and urged her to leave. But she didn’t. She stayed operating the siren and calling residents when the flood struck with force.

It filled Nellie’s house with water up to one and a half feet from the ceiling. It collapsed one part and tore the rest of it off its foundations and pushed it up against some nearby trees.

Rescuers entered the wreckage after the water subsided to find Nellie safe. She had climbed on top of her switchboard to ride out the calamity.

Often times telephone people were involved in heroic and creative efforts that were not connected with restoring telephone service.

Newspapers showed photographs of ten- and twenty- foot snow drifts in the town of Cheyenne, Wyoming. It was the infamous blizzard of 1949 that stopped everything across the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. Autos were stranded with people still in them; trains were snowbound; farms and ranches were isolated.

Imagine how those stranded people felt when they heard the whine of the telephone company’s snow-buggy and saw it gliding toward them over the drifts. The employees of Mountain States Telephone Company operated the snow buggy for several days, shuttling back and force carrying stranded people to safety and to hospitals.

In 1928, the pilot of a small single engine U.S. mail plane flew into a sudden blizzard over western Nebraska. He knew he couldn’t make it to his regular destination of Sidney. He was low on fuel and his plane was bucking against the wind and snow. It was night time and he descended looking for a place to make an emergency landing. At the lowest possible level He kept circling, fearful of descending too low and yet unable to make out anything let alone a flat space that would be safe enough to touch down.

Then he almost couldn’t believe his eyes. It looked like a flare being lit below, on the ground. Then there was another, then another.

Flares were being lit in numbers. He could see they outlined a small flat field that he could attempt his landing.

Mabel White was the only operator on duty in Potter Nebraska that night. She heard the plane circling low overhead. The mail plane’s regular flights passed over Potter. Mabel figured out that he was in trouble and called the airfield in Sidney. She got instructions of what should be done and called a local garage mechanic who hustled out and organized the “flare party.”

The pilot landed safely. The next day he was able to refuel and take off, continuing his mail deliveries to Sidney and North Platte.

The people in the four stories above were each awarded a Vail Medal and a cash award for their extraordinary efforts.

There are thousands more documented stories like these and probably even more unrecorded except in the memories of the people affected.

We were a culture. We were a monopoly. We were Ma Bell. We contributed to the well being of our neighbors as we did our work—person to person.

Categories: Don Warsavage - Person to Person